Everything You Wanted to Know About Oak (and Probably Some Stuff You Didn’t).

July 6, 2011Oak plays a bigger role in winemaking than I think most people realize! The color, flavor, tannin and texture of a wine can all be influenced via oak contact; either during the fermentation or aging of wine.

When it comes to white wines, oak is often viewed as “fruit killer”, and should never be allowed anywhere near the juice. However for the longest time, those with this opinion could been viewed as a small minority.

It used to be that producers around the world were over-oaking their wines; this in order to disguise cheap/bad grapes. Over the past few years, a consensus seems to have formed amongst the wine drinking population that oak-influence (at any level in a wine), should always be frowned upon.

To some degree I can get on-board with this statement. This doesn’t in any way mean to insist that oak in wine is always a bad thing; but think of it the same way you would of salt and pepper in cooking. A little will bring the dish alive. Too much and it will completely kill it.

The nuances of vanilla, spice, nuts, caramel, cream, toast, butter etc. that oak can give to wine, can enormously increase the wine’s complexity. Don’t say a wine is "too oaky" just because you can taste a slight oak character in your glass of Chardonnay. Say it’s too oaky if all you can taste is oak! If drinking that glass of Chardonnay it’s like chewing on a toothpick!

Where did the oak backlash come from?

The problem with oak started back when many winemakers (Australia and California particularly) discovered they could mask the lack of fruit or flavor in their wines (Chardonnay more than any other varietal) by using oak in some form.

Consumers would enjoy a “nutty” and “richly-flavored” wine, without realizing they were simply drinking fermented grape juice, which tasted of very little on its own. The over-oaking of wine was widespread; but since a quality oak barrel is very expensive, cheaper methods were investigated (see below section on Oak Chips).

Around the same time that oak contact was at its peak, a wine from New Zealand called Cloudy Bay caught people’s attention. A pure Sauvignon Blanc: crisp in acidity, light in body, very fruit-forward, and totally unexposed to oak. The result, for the most part, was the polar-opposite of what everyone else was doing with their white wines, and people seemed to like it.

And so the backlash slowly began…

A wave of unoaked wines started to appear on the market. Fresh wines which tasted of the grapes they were made from, rather than what the winemaker had added. Before long everyone in New Zealand was making unoaked Sauvignon Blanc, as the Kiwis believed that for some reason everyone in the world had just really started to dig NZ SB’s!

Not-quite! I think it’s more that consumers were responding to a white wine without oak!

Why oak?

Why oak?

Throughout history, different types of wood, including pine, chestnut and redwood, have all been used in making wine barrels, especially fermentation vats. However few wood-types possess the same properties as oak. It’s water tight, yet porous enough to allow the wine to evaporate slightly, (apparently up-to 6.5 gallons of wine can evaporate from a barrel in a year). This evaporation of mainly water and alcohol concentrates the wine, harmonizes the different flavors, and allows minute amounts of oxygen to pass through, thus softening the tannins. The shape of oak barrels also makes it extremely strong, and once on its side, can be moved by rolling, even when full.

So where does wine barrel oak come from?

Oak can also be sourced from different areas, but France and America are the most popular, with also being sourced from Eastern Europe. Oak from certain forests in France (Limousin and Vosges for example) is particularly prized and therefore very expensive. American oak tends to give a more intense flavor, and is much favored in the Rioja region of Spain. More recently, winemakers have even experimented with Chinese oak.

What is toasting?

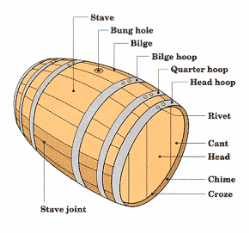

The individual wood slats that form a barrel are called staves, and they must be bent into shape before they are assembled to form a barrel. In order to do this, the barrel-maker (called a Cooper) heats them over an open fire. This is referred to as toasting, and obviously the longer the wood is exposed to the flame the more toasted it becomes.

(See the nerdy picture on the left that I took whilst I was out in Napa, of all the different toast levels which can be applied in a barrel.)

Because it’s the toasted surface of the wood that comes into contact with the wine, and because toasting influences the flavors imparted to the wine; the degree of barrel toasting is a very significant factor. At the extremes, heavy barrel toasting can impart a caramelized taste to wine, whilst a light toast might impart a subtle hint of vanilla, smoke, nuttiness or yes, even toast.

Age in barrel

It wouldn’t be any surprise to suggest that a wine aged in oak for a longer period of time will have more oak flavors. The general rule of thumb is the "bigger" (i.e. more full-bodied) the wine, the longer it will spend aging in barrel. There are a number of factors that influence a winemaker’s decision as to how long to leave the wine in barrel. If the final product is to be a blend of grape varieties, such as a Bordeaux or Chianti, the winemaker must decide if they want to blend the individual wines together either before or after putting them into barrels to age. If they are aged separately, the winemaker must decide how long to leave each separate wine in wood to achieve the desired taste or style, before they are actually blended together. This is obviously a complex series of decisions, and needless to say a winemaker must monitor (taste) the developments carefully.

What is the cost of a wine barrel?

What is the cost of a wine barrel?

The cost of a wine barrel can vary greatly depending on the type of wood it’s made from.

A French oak barrel can cost more than $900 each (with the price obviously varying based on exchange rates). American oak is less expensive, costing up to $400. Barrels from Eastern Europe are said to cost about $600 each. Of course these prices vary greatly depending on the cooperage.

Due to the high price that wine barrels command, most wineries can’t afford new barrels every year, although all the good wineries try to purchase a certain percentage of new ones. Therefore, barrels are used more than once (the upper limit is 5 times) and each time a barrel is used, it has fewer and fewer properties remaining to give to a wine. Think of it like a tea bag; the more you use it the weaker the results.

Why would you pay so much more for French oak than American oak?

American oak has wider grains and contains a higher percentage of "vanillin"; this is thought to impart more of a vanilla and "oaky" taste. Typically if winemakers are using American oak, it is on bold red wines or fuller bodied Chardonnay’s. French oak has a tighter grain, contains more tannins and flavor components, and is thought to impart less of a obvious "oaky" flavor.

While the majority of winemakers would side with French oak, wineries such as Silver Oak, Ridge and Beaulieu are known to use 100% American oak for aging their red wines.

Being that oak is so expensive, are there any other options than to age wine in oak?

Being that oak is so expensive, are there any other options than to age wine in oak?

This might come as a surprise to a lot of people, but in order to speed things up and lower the cost, oak chips (see picture to the left) can be added by the winemaker either during fermentation or during aging. Oak chips can impart a sense of oak aging in a matter of weeks, rather than the months need by regular oak barrel aging.

Other options available to the winemaker, include oak staves which are dropped into the wine either during fermentation or aging, or oak powder. The problem that you run into with both these methods is that oxygenation (as previously mentioned) does not occur as it does with oak barrels.

So what do you know, some genius came along and invented "micro-oxygenation"! This process pumps small bubbles (so small you can’t even see them) through the wine, and gives the same oxidative effect as a wine that has been aged in oak. These two processes combined saves a good deal of money, and allows some of the cheaper wineries to produce wines that taste two to three times the price! Crazy, right!?!

It’s also worth noting that the use of oak chips fairly recently (2006) became legal in Europe; therefore every winemaker has the option available to them. You can of course be sure that if they are doing it, they won’t be inclined to tell you (on the label)!

Now don’t go thinking that the use of oak chips is limited winemaking! Brandy-makers have been doing it forever! In the Brandy industry, a substance called Boise (oak essence) is used, which cuts the aging time, and is far cheaper than using a barrel. Anyone who has consumed very cheap brandy may well have noticed an intense caramel flavor caused by adding Boise, burnt sugar or just caramel itself to the base spirit.

It should be recognized that wines made using oak chips or most of the other “cheating” methods do not age as well, or for as long as those made in the “traditional-style”.

To Conclude

I firmly believe most wine lovers will agree that oak is important when it comes to making wine. What they disagree on, however, is how much oak. It is very much still a matter of personal taste. What I hope this post shows you is that there is a much more to oak than just the length of barrel aging a wine experiences!

This entry was posted in News and tagged American Oak, French Oak, Micro-Oxygenation, Oak, Oak Chips, Unoaked, Wine Barrels. Bookmark the permalink. ← Wine Lingo – Chewy Trinitas Carneros Pinot Noir 2009 Paired with Cedar Plank Sockeye Salmon →